J.S. Bach

I grew up Lutheran — the Scandinavian version of Lutheranism, more evangelical but less academic and liturgically sophisticated than the German version. J.S. Bach is revered as a saint by the latter group, but we never heard of him, though we frequently sang hymns which were adaptations of chorales harmonized and arranged by him, from his passions and cantatas. The sound was definitely in our ears, but we didn’t know its origins.

Bach figured prominently in my college music history survey, and I struggled through several movements from his B Minor Mass in the Chapel Choir; but that was all I knew about Bach until I moved to Chicago after college and began singing his music with various groups, particularly with the Rockefeller Chapel Choir, which presented an oratorio series each year, covering major works by Handel, Bach, and other composers. I sang my first complete B Minor, with orchestra and soloists, with the Rockefeller Choir — and was transfixed. In those days, the choir and orchestra were able to fit in the balcony at the back of the chapel, high above and behind the listeners in the pews below. It was a superior acoustical space, and the sound heard downstairs was glorious. I remember sharply, clearly, my out-of-body experience singing that incredible work, with that fine choir; it felt as though the roof had lifted off the chapel and I was at one with the stars in heaven.

Soon after that experience I began coaching with Richard Boldrey at North Park College, and we immediately set to work on the bass arias from the B Minor. Though he did not profess to any knowledge of Historically Informed Performance Practice (HIPP), Richard was an excellent musician and teacher, and I learned a lot about making my way through a Bach score with him.

In succeeding years I spent eight summer sessions at the Oberlin Baroque Performance Institute, and another ten or so singing with the Oregon Bach Festival, where I became acquainted with a large number of Bach’s cantatas, and participated in many performances of the John and Matthew Passions and the B Minor. I have since conducted several performances of all three with Chorale, and with the Rockefeller Choir during the years I was employed there.

Bach’s motets occupy a unique niche in his output. It appears that most of them were composed for funerals, and lack independent continuo or orchestral parts — presumably so they could be performed outdoors, at the graveside, without instruments, or indoors, with instruments simply doubling the choral parts. This optional unaccompanied procedure was already outmoded in Bach’s time, harking back to Renaissance performance practice of some 200 years earlier. But Bach was familiar with music from that earlier time, and adapted aspects of it in his choral compositions. He also utilized the Venetian polychoral texture which appears in some of these motets, developed by Giovanni Gabrieli and others at St. Mark’s in Venice during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

It is difficult to keep all the forces required by such a complex texture synced, without the solid underpinning of an orchestra and continuo — but this has been Chorale’s practice since the beginning when we perform these works, and we don’t feel the music suffers, so long as we work conscientiously to keep things clean. Chorale’s tradition has been to perform unaccompanied since our founding, back in 2001. The discipline required to do this defines our sound, and makes us the choir we are.

We hope you will come to hear us sing motets by Bach and Anton Bruckner, and piano quartets by Johannes Brahms, on June 8, 3 PM, at St. Thomas the Apostle Church, in Hyde Park.

Anton Bruckner & Bartlett Butler

Anton Bruckner Bartlett Butler

I first encountered the music of Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) during my second year in college. Though I had moved up to the “A Choir” (called the Nordic Choir) at the end of my first year, I maintained a relationship with the B Choir (called the Chapel Choir), mostly because of the group’s conductor, Bart Butler. Primarily a historical musicologist, he programmed first-rate repertoire for us — both because he loved it, and because he felt a pedagogical obligation to introduce good music to his students, many of whom were music ed majors and would be teaching music someday.

My college was noted for the high quality of it’s choral offerings, but that quality didn’t reflect good repertoire so much as it reflected outstanding choral technique and discipline, group cohesion, and the ability to appeal to our constituency and to recruit students (and money) for the college. The music we sang was not schlock, but I would not program most of it, myself.

I was not unusual; I wanted the reward and recognition that came with singing in the A choir, wanted the polish and shine that were part of that experience, wanted to go on extended tours. Like other first year singers, I treated the B choir year as a necessary step on the way to the A choir.

But even during that first year, I realized that there was something very special about what Bart Butler was offering. I didn’t grow up in a musically enriched environment, didn’t attend concerts (other than the school programs I sang in), didn’t listen to recordings of classical music. That first year, in the Chapel Choir, introduced me to sounds and musical ideals I hadn’t previously known existed. We sang Bach, Palestrina, Schütz, Vaughan Williams, Brahms, Purcell, Byrd, others I don’t recall. Many of my fellow students were unimpressed, but I was completely hooked, mesmerized. In the following years, I would go and listen to Chapel Choir rehearsals, in love with the repertoire, then return to sing with the Nordic Choir, in love with our success.

During that second year, Chapel Choir sang Os justi, by Bruckner. I attended rehearsals during which the singers struggled to come to terms with Bruckner’s angular melodic lines, his explosive emotionalism, his extreme contrasts of dynamics and tessitura, his meltingly beautiful harmonies in one passage suddenly interrupted by a strident, rhythmically compelling phrase in the following measures. This was impolite music that grabbed me by the heart and wouldn’t let go. It pulled me in, and I have been a Bruckner devotee ever since. Primarily a composer of large symphonies, Bruckner composed only a handful of motets, as an adjunct to his profession as a church musician; but they are among the best, perhaps the best, sacred choral music composed in the nineteenth century. Chorale will sing a number of them, including Os justi, on our June concert.

I’m sure I would have encountered Bruckner on my own at some point; but I feel a deep and lasting gratitude toward Bart Butler for introducing me and a generation of college students to him, and to many another composer whose music has become my daily bread over the course of my career.

Kit Bridges, pianist

Chorale’s spring concert has a hefty title: The Four B’s: Bach, Bruckner, Brahms, and Bridges. “Bridges” refers to our pianist, Kit Bridges, who will perform Brahms’ Four Quartets for Four Voices and Piano, opus 92, with Chorale, as a major portion of our program. Completed in 1884, these quartets showcase the composer’s brilliant and idiomatic writing for piano (Brahms was an accomplished pianist himself), which in turn showcases Kit’s brilliant playing, too seldom heard in the context of his role as Chorale’s rehearsal accompanist.

I first became aware of Kit when I was a new graduate student in voice at Northwestern University. I arrived on campus with no particular strategy or goals, other than earning an advanced degree which would allow me to teach on the college level. I had not investigated the school’s voice teachers nor secured a spot in one of their studios, and was not at all aware of who the pianists were — I was really green, and was assigned whoever was left after the more strategic students had laid dibs on the desired situations. It didn’t take me long to realize I had made a mistake, that not all teachers and pianists were alike. However naive I was about the process, I was not naive and unformed when it came to musical taste and goals; and I didn’t fit well where I had landed.

Attendance at studio and degree recitals was a necessary part of my graduate school experience, and I soon became aware of who was doing what I liked. Kit was the regular accompanist for one of the voice studios, and I only had to hear him once to realize that he was the pianist/collaborator for me. He played with personality and conviction, warmth and mystery, and had the chops to handle whatever the singers threw at him. He was supportive and responsive with singers, but never neutral. He was the real deal: a top flight pianist who actually enjoyed working with singers. I wasn’t able to collaborate with him, myself, until I had finished my degree — but once I had, the dam broke, and I seldom performed, at least in Chicago, with any other pianist after that.

I participated for a couple of summers in a program called “International Festival of the Art Song,” held on the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. It consisted of a week of masterclasses, plus a number of recitals, presented both by the master teachers (Gérard Souzay, Elly Ameling, and Dalton Baldwin were the artistic core of the festival) and by selected students. My first year, I went alone, and was assigned a pianist — again, not realizing that this was something I should have strategized in advance. My first time up, we sang and played Fauré’s “En sourdine”, which begins with a few bars of piano introduction. We had barely begun — I don’t think I had sung a note — when Dalton sighed, asked the pianist to move over, sat up to the keyboard himself, and played it through while I sang. I was in heaven. This was music; this was collaborative art, between singer, pianist, poet, and composer. I had never personally experienced anything this magical, and I was hooked. The pianist matters, is an equal partner. I ended up going to France to study with Souzay and Baldwin; I also ended up returning to the festival the following summer with Kit in tow. On the purest, highest plane, this is why I do music. Dalton was so impressed with Kit, he suggested we make a CD (we never did; I never felt up to Kit’s standard). Over the following years, Dalton chose concert programs for us, pianistically challenging works by Schumann, Schubert, Wolf, Brahms — he felt Kit was particularly good in this repertoire. I remember once when we were working on some Mahler, his playing was so beautiful I broke down in tears — I couldn’t believe I was part of something so transcendent.

Kit and I have worked together now for nearly forty years. He is never less than wonderful; he is at his best in Brahms. Come and hear what he does with us! June 8, 3 PM.

Rejoice in the Lamb

Benjamin Britten in 1938.

Benjamin Britten, composer, conductor, and pianist, was a central figure in 20th-century British music. He composed in a broad range of genres, including opera, orchestral and chamber pieces, choral and solo vocal works, and film music. Recurring themes in his operas include the struggle of an outsider against a hostile society and the corruption of innocence— themes upon which his festival cantata, Rejoice in the Lamb, is also based.

Rejoice in the Lamb was composed for the 50th anniversary of St. Matthew’s Church, Northampton on September 21, 1943. The vicar, Walter Hussey, a notable patron of the arts, wrote in the program notes for the work’s first performance:

The words of the Cantata—“Rejoice in the Lamb”—are taken from a long poem of the same name. The writer was Christopher Smart, an eighteenth century poet, deeply religious, but of a strange and unbalanced mind.

“Rejoice in the Lamb” was written while Smart was in an asylum, and is chaotic in form but contains many flashes of genius.

It is a few of the finest passages that Benjamin Britten has chosen to set to music. The main theme of the poem, and that of the Cantata, is the worship of God, by all created being and things, each in its own way.

The Cantata is made up of ten short sections. The first sets the theme. The second gives a few examples of one person after another being summoned from the pages of the Old Testament to join with some creature in praising and rejoicing in God. The third is a quiet and ecstatic Hallelujah. In the fourth section Smart takes his beloved cat as an example of nature praising God by being simply what the Creator intended it to be. The same thought is carried on in the fifth section with the illustration of the mouse. The sixth section speaks of the flowers—“the poetry of Christ”. In the seventh section Smart refers to his troubles and suffering, but even these are an occasion for praising God, for it is through Christ that he will find his deliverance. The eighth section gives four letters from an alphabet, leading to a full chorus in section nine which speaks of musical instruments and music’s praise of God. The final section repeats the Hallelujah.

The original poem was a lengthy work entitled Jubilate Agno. The extant manuscript was not discovered until 1939, and is not complete. Its discoverer, William Stead, published the fragment under the name "Rejoice in the Lamb." Poet W.H. Auden brought the poem to Britten’s attention, and Britten was immediately attracted to its color, drama, bizarre imagery, and the central issue of the individual against the crowd, or against authority. Britten chose ten of the most celebratory and religious sections to set to music. While there is a mad, whimsical atmosphere to the poem, and to Britten’s setting, the religious character of the work is also striking throughout. The closing “Hallelujah” includes some of Britten’s most memorable music for chorus.

Vaughan Williams’ Mass in G Minor

Ralph Vaughan Williams, c. 1921

The longest, most magisterial work on Chorale’s March 23 concert program is Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Mass in G Minor.

Andrew Carwood conductor of the choir of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, writes, “Vaughan Williams’ Mass in G Minor... was the first substantial, unaccompanied setting [of the mass] to be written with a distinctly English voice since the time of William Byrd in the sixteenth century.” The power and scope of the work continue to be remarkable, more than 100 years after its premiere.

Vaughan Williams was the most important English composer during the years between Purcell and Britten. His distinctive style expresses his love of native English resources—both popular folk music and the highly developed church music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—and a personal, visionary spirituality, outside of, but still related to the traditions of the English church.

The Mass was composed in 1920- 21, shortly after the end of World War I. Vaughan Williams was already an established composer, with an extensive body of work behind him, before enlisting in the war effort. He served as a wagon orderly with the Royal Medical Corps in France and on the Salonika front, later returning to France as an artillery officer. Many of his friends and contemporaries perished in the war, and from his vantage point in the medical corps he surely saw much that sobered and deepened his thinking. His second wife, Ursula Vaughan Williams, wrote that “he was an atheist during his later years at Charterhouse and at Cambridge, though he later drifted into a cheerful agnosticism: he was never a professing Christian,” and his wartime experiences did not alter this. Nonetheless, the series of works written 1919-34 suggest, in their subject matter and depth of feeling, a reaching out towards a spiritual view of reality, as well as a deep sense of the tragedy and futility of the war.

Vaughan Williams utilizes an early Baroque polychoral texture, in which the three choirs— two equal SATB choruses, and an SATB solo quartet—call and respond antiphonally, as well as accompany one another. At the same time, he favors pre-diatonic harmonies and quasi-gregorian melodic figures, which imbue the mass with a timeless, elegiac quality. The listener is always aware of Vaughan Williams’ love of the English pastoral tradition—his melodic lines, sometimes stepwise and undulating, sometimes surprisingly jagged, seem to spring directly from the indigenous English folk music he collected and studied throughout his career. At the same time, one cannot escape the dark, tragic quality of the music—though always soothing, it is never joyous or innocent. The landscape, the history, the people it evokes, are indelibly watered with the blood of the millions of victims of World War I.

I first became aware of the Mass when I was a student at Luther College, in Decorah, Iowa, singing in the school’s choir. The Roger Wagner Chorale, one of America’s premier professional choirs at the time, had recently issued an LP of the work, and was scheduled to perform it at our college during their concert tour. Our conductor, Weston Noble, had also programmed it for us, and we were deeply into learning it when the Wagner Chorale performed it on our campus. I sang in the solo quartet (octet, in our case), and felt deeply, emotionally involved with the work. We took it on tour, ourselves, and the experience of singing it night after night profoundly affected me. Singing this work was the most significant experience of my musical life up to that point. Returning to it now, many years and musical experiences later, I am not disappointed. It was not an adolescent crush; I really love this work, and am glad to have this chance to experience it again.

Chicago Chorale presents English Masterpieces

When I started Chicago Chorale, in October 2001, I was coming off a career conducting college and university choirs, which I had begun back in 1977. My point of departure had always been pedagogical – repertoire that students should learn, and that represented the interests of the various institutions for which I worked, drawn from a wide variety of sources. My experiences as a freelance singer had been very different from this – I sang whatever the conductor in question required, in churches, in synagogues, with orchestras, with early music ensembles. I had tried to make use of those professional experiences in my teaching, but was always constrained by the age and experience of my singers, by the resources provided by the schools, and by my pedagogical mission.

To start out on my own, with no money, no physical home, and only the good will of singers I could convince to sing for me, was daunting, not only because of our poverty, but because we suddenly had no mission, no raison d’être: we had only ourselves, and a small audience of friends, to please and to program for.

It took us several years to figure out who we were, what we were suited to, what would attract, challenge, and satisfy audiences. With the understanding that we will perform only music that we really believe in, we have explored Renaissance polyphony, German Baroque passions and masses, massive Russian liturgies, nineteenth and twentieth century a cappella motets in a variety of languages and national styles, and music representing specific ethnicities. We have sung Norwegian and Icelandic music, Baltic minimalism, Argentinian tango, Native American and African American music, and Gregorian chant; French and English music; time-honored classics and recent compositions. We have commissioned new music.

Along the way, we have become who we are, sharpened our craft, and gained insight into what constitutes music that matters and persists.

Our winter concert features music by three seminal twentieth century English composers: Benjamin Britten, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Herbert Howells. Organist David Jonies, Director of Music at Chicago’s Holy Name Cathedral, will join us for Britten’s Rejoice in the Lamb, a setting of the poem “Jubilate Agno" by visionary poet Christopher Smart, and a tour de force for both choir and organist. This will be preceded by Herbert Howells’ heart-rending setting of Psalm 42, Like as the hart desireth the waterbrooks, also with David at the organ. The balance of the program will feature Ralph Vaughan Williams’ a cappella Mass in G, for double chorus, and the short but powerful anthem Bring Us, O Lord God, by a lesser-known contemporary of these composers, William Harris.

Yes, this program can be enjoyed through pedagogically prepared ears, as an extension and rounding off of the English program we presented two years ago, featuring major composers we steered clear of at that time. But it can also be enjoyed as a celebration of the very best produced by that tradition at the very peak of its brilliance, on its way toward a new era. We love this music, whatever its significance, and we know you will, too.

Welcome to Chicago Chorale’s 2024-25 Season

Chicago Chorale’s 2024-25 season is just around the corner. Work has gone on through the summer months, choosing repertoire, ordering music, reserving venues, hearing auditions, and preparing print materials to promote the season.

Our autumn concerts focus on repertoire of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, from Scandinavia and the Baltic states. I am particularly drawn to this repertoire, perhaps because of my own Norwegian heritage; but I also find that the extraordinarily high level of choral performance in that region of the world inspires composers to write challenging, multifaceted music for virtuosic a cappella choirs. This is just the performance genre to which Chorale aspires.

A significant portion of our concert will be devoted to works by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, whose influence has in many respects transformed choral writing in the 21st century. We will also also sing two selections from Edvard Grieg’s final composition, Fire Salmer, Opus 74, which precedes Pärt’s work by a century, and was as revolutionary in its own time, as Pärt’s music is today. The program will also include works by Knut Nystedt, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Urmas Sisask, Otto Olson, and Ēriks Ešenwalds, along with a couple of folk song arrangements by Swedish composer Gunnar Eriksson.

Our winter concert features music by three seminal twentieth century English composers: Benjamin Britten, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Herbert Howells. Organist extraordinaire David Jonies, Director of Music at Chicago’s Holy Name Cathedral, will join us for Britten’s Rejoice in the Lamb, a setting of the poem “Jubilate Agno" by visionary poet Christopher Smart, and a tour de force for both choir and organist. This will be preceded by Herbert Howells’ heart-rending setting of Psalm 42, Like as the hart desireth the waterbrooks, also with David at the organ. The balance of the program will feature Ralph Vaughan Williams’ a cappella Mass in G, for double chorus.

In June, you will have a chance to hear Chorale’s regular pianist, Kit Bridges, in a featured role, playing Johannes Brahms’ Four Quartets, Opus 92, for choir and piano, and Kit’s own arrangement of the final movement of the Neue Liebeslieder, Opus 65, Nun, ihr Musen, genug! A graduate of Northwestern University and former faculty member at DePaul University, Kit has long been recognized as one of the premier collaborative pianists in Chicago; I frequently shake my head in disbelief at our door fortune to have him at Chorale rehearsals, leading and teaching by example from the keyboard. The concert will open with three motets by J.S. Bach: Ich lasse dich nicht, Komm, Jesu, komm, and Fürchte dich nicht, ich bin bei dir, and include a set of motets by Anton Bruckner, my favorite 19th century composer of sacred choral music.

A special treat with this blog entry, to whet your appetite for the coming season: a video filmed and recorded at Monastery of the Holy Cross, of Chorale singing “God is Seen,” an American hymn from the Sacred Harp tradition, arranged by Alice Parker and Robert Shaw.

I look forward to seeing you at our concerts!

Choral Music of the Americas - Chorale’s Latin Set

Sydney Guillaume, Composer & Conductor

A little more than a year ago, Chorale sang a concert which included music by three Argentinian composers: Carlos Guastavino, Astor Piazzolla, and Martín Palmeri. Of the three, Guastavino was the most conservative and European in style; some have called him “the Schubert of the Pampas.” He expressed support for developing an Argentinian national style, including Argentinian texts and indigenous elements, but his music does not reflect much of this. Piazzolla on the other hand embraced the popular, African-based tango of the working classes, and developed it into a distinctive, sophisticated style. Martín has followed largely in Piazzolla’s footsteps. The Caribbean and South American composers on our current program exhibit a similar dichotomy.

Venezuelan composer César Carrillo was born in Caracas in 1957. His first musical influences came through his involvement in traditional music ensembles, where he sang both as a soloist and as a back-up singer, and learned to play many traditional instruments. He later veered toward a more centrist European-based style, particularly in his church music, which tends to be settings of Latin liturgical texts. Widely recognized in his own country, he has produced a sizable body of choral work, much of which is published and performed in the United States. The lovely, a cappella “O magnum mysterium” which Chorale will sing, is his best-known work in this country.

Miguel Matamoros (1894 -1971) was a popular Cuban musician and composer, and founder of the Trío Matamoros in Santiago de Cuba. He is known for being an author, composer, and performer of popular songs, and contributed notably to the development of traditional, rural Cuban music into an Afro-Cuban genre. He particularly focused on the bolero, a popular Latin American vocal and dance style. “El juramento” (The Oath), the bolero which Chorale will sing, is one of his best-known songs, and has been arranged for SATB choir by Elenco Silva.

Sydney Guillaume (b.1982) originally from Port-au-Prince, Haiti, came to the United States when he was 11 years old. He received a bachelor’s degree in music composition from the Miami Frost School of Music, and has composed a large number of choral pieces reflective of his Haitian background. The text of “Dominus Vobiscum” (God be with you), the piece we will sing, was written by his father, Gabriel T. Guillaume, in Haitian Creole, which derives its linguistic roots from French. Unlike the more formal Latin Christian music of Carrillo, which seems to inspire its composer to employ conservative harmonic and rhythmic language, Guillaume’s music glories in exhilarating African rhythms and archaic, modal harmonies.

It’s a wonderful experience for us to prepare this music which is so far out of our usual wheelhouse. Please come and hear what we do with it! June 1st in Lincoln Park, June 2nd in Hyde Park. We’d love to see you there.

Chicago Chorale Welcomes New Managing Director

Greetings!

I am thrilled to announce my new role as Managing Director of the Chicago Chorale! Honored to follow in the footsteps of the Chorale's esteemed Managing Directors, I am eager to contribute to the legacy of this remarkable family. Drawing from my background in non-profit program management and performance, I aim to merge these experiences to bolster the Chorale's standing in both the Chicago and Choral Arts communities. With the guidance of Bruce Tammen, the Chorale's Founder and Artistic Director, and the support of our governing body, I intend to explore avenues for growth, expand our presence into new realms, and curate choral experiences that resonate with both our loyal supporters and new, diverse enthusiasts.

As the arts landscape undergoes significant transformation globally, I have observed firsthand the impact of societal dynamics on artistic expression. I am committed to navigating these shifts while upholding the Chorale's commitment to excellence. By fostering dialogue between tradition and innovation, I aspire to contribute meaningfully to the cultural conversation. As I shared with Chorale members upon my introduction, I approach leadership from an artist's perspective, driven by a passion for creating impactful work.

I am grateful for the warm welcome thus far and eagerly anticipate the exciting journey ahead with the Chicago Chorale.

William Powell, III

Thoughts about the Development of American Music

In the grand scheme of things, the 500 years since Europeans and enslaved Africans began settlement of the Western Hemisphere has been very short. The cultures they brought with them— the art, music, technology, religion, social structure, foods, all of that— reflected many centuries, even millennia, of development on the Eastern side of the Atlantic Ocean. All of the new countries that eventually were constituted on our side of the ocean had to deal, to varying degrees, with the clash, the mixing, of these disparate European and African cultures, and with the indigenous cultures already in place.

Christianity, in many of its manifestations, was a dominant front in this invasion, bringing swift and cataclysmic change. Broadly generalizing: British settlement of the Eastern seaboard brought several versions of protestantism; Spanish and Portuguese settlement of Central and South America, as well French Canada and the southwestern portion of the United States, brought Roman Catholicism. Scandinavians and Germans brought Lutheranism to the Midwest. Africans were not allowed to practice their religions openly, but aspects of their native religious practice informed the development of African American culture as surely as the Christianity which was forced upon them.

Each of these groups brought established musical practice and repertoire from its region of origin. Long before the arrival of refined Western European concert music, the new Americans were making both sacred and secular music, mostly based on the European music with which they were familiar. North American Protestant church music, typically sung by members of the congregation in a variety of European languages, gradually came to be sung in English, which brought it into the mainstream. Roman Catholic music, because it was sung in Latin by smaller, trained choirs, was much slower to adapt to the broader culture. Secular music— what we are likely to call folk music today— quickly adapted to cultural change, developing into something new and less European.

Beginning about mid-twentieth century, composers, arrangers, and conductors, reacting to the predominance of formal Western European art music in American concert life, began to pay serious attention to this “roots” American music, and sought to develop a music that was more reflective of the American experience. Two of the most important people in this movement in the United States were Robert Shaw (1916-1999) and Alice Parker (1925-2023). Together, they discovered and researched hundreds of North American songs, from a variety of sources, and arranged many of them for SATB choir. I heard Mr. Shaw say, in a question and answer session during a Carnegie Hall choral workshop, that Ms. Parker, a talented composer herself, did most of the arranging, remaining scrupulously within the harmonic and melodic framework of the original materials while creating high quality choral works for modern ensembles. Mr. Shaw, a conductor, primarily advised her on what would work with audiences, what would make performances “pop.” Their arrangements, some of them from as early as the late 1940s, continue to be in print, and have sold millions of copies throughout the world, effectively defining the genre. Chorale will sing three of them in our upcoming concerts: Hark, I Hear the Harps Eternal, Wondrous Love, and My God is a Rock. The first two are from the Sacred Harp hymnal of early American hymns; the third is an African American spiritual.

Choral Music in the Americas

The idea for Chorale’s current project, “Choral Music in the Americas” came to me over a year ago, while I was watching the “White Lotus” HBO series. Intrigued by the first season’s Hawaiian background music, much of it arranged for choir, I contacted a friend with ties to the Twin Cities-based group “The Rose Ensemble” (since disbanded), which had performed and recorded the music. She referred me to their recordings and scores. I listened, perused, and decided that these pieces, though appropriate for the series, would not work for Chorale. In the process of working through them, however, it struck me that this music from the Pacific islands was American Choral Music, and that I had never before thought of it in that light. This set me to thinking about the far-flung nations and cultures that should be considered under the umbrella of American choral music— a vastly broader spectrum of choral expression than I had previously considered.

At the same time, Chorale was performing Misatango, by Argentinian composer Martin Palmeri. My background reading about the tango genre impressed upon me the role that synthesis and hybridization have played in the development of American music of all types, from the Atlantic to the Pacific and the Arctic Circle to Tierra del Fuego. These developments have taken shape in fairly recent times, as the result of wave after wave of immigration and conquest, and our musics reflect these waves, and the new cultures that have resulted.

I knew I could touch on only a fraction of all this in a single concert, but I thought I’d take a stab at presenting representative sources, composers, and arrangers, which contribute to the kaleidoscopic whole we call American music.

North Americans are most aware of the British/Scottish/Irish settlement of our east coast, from New England down to Georgia. These settlers brought both sacred and secular music with them, which will be represented in our program by two arrangements from the Sacred Harp hymnal, plus an arrangement of the well-known sea chanty, Shenandoah. These arrangements are as much part of our history as the original source material, demonstrating the interpretations of these European sources by modern, American ears.

I have chosen three contemporary, original compositions from the Caribbean and South America: from Cuba, El juramento, by Miguel Matamoros; Venezuela, O Magnum Mysterium, by Cesar Carrillo; and Haiti, Dominus Vobiscum, by Sydney Guillaume. Turning next to Canada, we will present Vision Chant, an original composition by Cree composer Andrew Balfour, based upon an Indigenous chant style. This will be followed by Brier, a Good Friday motet, composed in 2004 by Jeff Smallman. Following these Canadian compositions, we will sing Let My Love Be Heard, by Minnesota composer Jake Runestad.

Central to our program will be Samuel Barber’s magisterial Agnus Dei, based by the composer on his well-known Adagio for Strings.

We’ll conclude with a set of three African American pieces. The first, My God is a Rock, is arranged by the team of Robert Shaw and Alice Parker. The second, The Word was God, is an original composition by Rosephanye Powell, an African American female composer. The third, Joshua!, is an arrangement of a traditional spiritual by African American composer Stacey Gibbs. They present three very different points of view on this important American genre.

Does this sound like a DMA lecture-recital? It won’t be, I promise you. Each of these pieces is compelling in its own right, and they fit together as an engaging whole. You’ll be proud you live on this side of the Atlantic.

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms, 1853

Chicago Chorale has performed a lot of music by Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) over the course of our history. Our CD, "A Chorale Christmas," features one of his motets, Es ist das Heil uns kommen her; we have presented the two piano/four hands version of his German Requiem; and we have sung various of his motets in combination with works by Bruckner, Mendelssohn, and Rheinberger. But all of that was several years ago; we have focused primarily on twentieth and twenty-first-century music since we last tackled him. This winter, though, we have returned to two of his most beautiful and famous a cappella works, Warum ist das Licht gegeben dem Mühseligen? and Ich aber bin elend.

Brahms, like Mendelssohn, was thought by his detractors to be conservative, even reactionary, in his own time. He adhered to time-honored forms and genres— "pure music"—while his contemporaries in the New German School veered in a more rhapsodic, freely expressive direction, often in response to outside, non-musical stimuli. Some critics found his music inexpressive and overly academic. Fortunately, better heads and ears prevailed: Brahms enjoyed a brilliant, highly-productive career, composing for symphony orchestra, chamber ensembles, piano, organ, voice, and chorus. His works in all these genres are performed regularly; his place on the A-list of historic European composers is secure.

Also, like Mendelssohn, Brahms grew up in a musical environment but on a different social plane. His father was a jobbing musician, playing both winds and strings; his mother was a seamstress. Recognizing his talent, his parents arranged musical training for him and encouraged him to pursue a performing career. He was energetic and independent, and, though he lacked the Rinancial backing and social connections enjoyed by Mendelssohn, he met inRluential people who would help him develop a successful career, as both pianist and composer.

Brahms' family was Lutheran, but he did not practice any religion as an adult. Nonetheless, he was well acquainted with the Bible and set numerous Biblical texts, both in his major German Requiem and in his numerous a cappella motets. As a young man, he studied a number of J.S. Bach's cantatas and often based his own motets on Bach's models. He composed Warum ist das Licht gegeben dem Mühseligen? in 1877 in memory of Hermann Göß, who had died after suffering from a prolonged illness. He reused musical material from an unfinished Latin mass, Missa canonica, which he had begun in 1856. Very much in Bach's style, he structured the motet as a series of three movements— including a fugue and a canon for six voices— followed by a harmonization of Luther's chorale, "Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin."

The second Brahms motet on our program, Ich aber bin elend, consists of a single movement for an eight-part double chorus and is probably the last choral work he composed (1889). Though brief in duration, it expresses the same fears, doubts, and hope for salvation that Brahms explores at greater length in the earlier Warum.

Felix Mendelssohn

Portrait of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy by Eduard Magnus, c. 1846

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) was recognized early as a child prodigy, compared to the young Mozart by contemporary observers. His father was a well-to-do banker, and the family environment was cultured and intellectual. Felix began taking piano lessons from his mother when he was six and played his first public concert at the age of nine. He began composing early, as well, and his compositions were performed in his parents' home by a private orchestra hired to play at their regular salons.

Mendelssohn's output eventually included symphonies, concertos, piano music, and chamber music, in addition to songs, oratorios, and church music. He is credited with "rediscovering" the music of J.S. Bach and bringing the major works of the hitherto forgotten master to the attention of his contemporaries. His oratorios, Elijah and St. Paul, are modeled more on the examples of Handel and Haydn than on Bach's masses and passions, but he clearly had Bach in mind while composing his many smaller choral motets.

Historian James Garratt writes that from his early career, "the view emerged that Mendelssohn's engagement with early music was a defining aspect of his creativity." In his composing, performing, and teaching, he sought to reinvigorate the musical legacy that had preceded him rather than replace it with new forms and styles.

The Leipzig Conservatory, which Mendelssohn founded in 1843, served as the bastion of conservative, traditional musical values throughout the 19th century. Mendelssohn's radical contemporaries Wagner, Liszt, and Berlioz, who constituted the "New German School," regarded the school and its founder as outmoded and unimaginative; Berlioz wrote of him that he had "perhaps studied the music of the dead too closely." Critical opinion of Mendelssohn has undergone revision in the 20th and 21st centuries; he is now universally acknowledged as one of the important figures of the Romantic period.

Mendelssohn composed his a cappella motet Denn er hat seinen Engeln befohlen, MWV B 53, in 1844, in response to an attempted assassination of Frederick William IV, King of Prussia, adapted it, with orchestral accompaniment, as the seventh movement of his oratorio Elijah in 1846.

Frank Martin: Sonorous and Satisfying

Chorale is swimming in deep waters this winter. Felix Mendelssohn, Johannes Brahms, and Frank Martin are giants in the world of Western music; performing their works requires skill, range, and humility. We have been working with them since January 3, and find there are no shortcuts; each speaks a language so distinct, complex, and compelling, that one wonders how we will have time and space to comprehend them.

The least-known of the three, Frank Martin (1890-1974), whose Mass for Double Chorus we will perform, was born in Geneva, Switzerland. His ancestors were French Huguenots who left France in the 16th century, and his father was a Calvinist minister. Primarily a pianist, Martin was largely self-taught as a composer, never attending conservatory. Rather, he attended Latin school and went on to study mathematics and physics at the University of Geneva for two years. Simultaneously he studied piano and composition with composer Joseph Lauber, who also introduced him to instrumental writing. Between 1918 and 1926 he lived in Zurich, Rome and Paris, working on his own, performing on harpsichord and piano, teaching, and searching for a personal musical language. After World War II he moved to the Netherlands, where he remained for the rest of his life.

The early years of the twentieth century were a period of extreme ferment and unrest in Western music. Martin’s unusually prolonged development reflects that turmoil, during which he studied and experimented with music that had preceded him, trying to find a place for himself and his ideas. Early on, he composed in a linear, consciously archaic style, reminiscent of fifteenth and sixteenth century sacred vocal music, restricted to modal melodies and perfect triads. Later in the same decade he enriched his harmonic and rhythmic palette through experimentation with Indian and Bulgarian rhythms and folk music.

In 1932 he became interested in Arnold Schoenberg’s work with 12-tone serialism. He incorporated some elements of this technique into his own musical language, but refused to abandon tonality altogether. Ultimately, he developed a strong personal style, strongly influenced by elements of German music, particularly that of J.S. Bach, and by the harmonic language associated with early twentieth century French composers, particularly Debussy and Ravel.

Martin composed his Mass in 1922, during this period of experimentation. He added the Agnus Dei movement in 1926. Though it precedes his encounter with 12-tone technique, the work clearly demonstrates other compositional ideas with which he was then grappling. Modeled after the liturgical masses of the Renaissance, with five movements corresponding to the five ordinary sections of the liturgy, it utilizes techniques typical of Josquin and his fifteenth century contemporaries, particularly paired imitation, where the words and melody of one segment of the choir are immediately echoed by another segment of the choir. Large chunks of imitative, almost fugato-like writing suggest the sound and texture characteristic of late sixteenth century composers Palestrina and Victoria; the double-choir framework upon which the work is built, where the two choirs are clearly differentiated from and juxtaposed to one anther, hark back to the seventeenth century Venetian style exemplified in the works of Giovanni Gabrieli.

Along with these historically conscious elements, we hear rhythmic and harmonic passages reflecting his awareness of non-western music, especially in the percussive effects produced by the second choir through incessant rhythmic patterns, and the presence of non-triadic harmonies, particularly open fifths and tritones.

Traditionally, musical settings of the Mass ordinary were intended for use during worship; through their evolution as a large musical form, mass settings evolved into concert works, typified at their peak of development by such masterpieces as Bach’s Mass in B Minor, which were not suitable for liturgical use. Martin, however, intended his work to function in neither arena; as he wrote in 1970, “I did not at all desire that the work be performed, believing that it would be judged entirely from an aesthetic point of view. I saw it entirely as an affair between God and me…. the expression of religious sentiments, it seems to me, should remain secret and have nothing to do with public opinion.” Upon completing his Mass, Martin put it away, never intending that it be heard publicly. He finally allowed it to be performed, in 1963, almost forty years after its completion, at the urging of his students. He considered it a youthful attempt on the way to his mature style; but modern audiences find it richly sonorous and emotionally satisfying. It is amazing that Martin refused to let it be published or performed for so long; it is now regarded as one of the pinnacles of the twentieth century choral composition.

It took Frank Martin many years before he was satisfied that he had found a musical idiom he could call his own. But he did achieve the difficult feat of creating a musical world balanced between conservative and avant-garde trends, which feels just right, in hindsight. And though his Mass came early in his development, it doesn’t sound like a work in progress, but stands as a fully-formed statement. I’m tempted to say it just took a long time for him to catch up with himself.

Music Makes Us Human

During orientation week of my first year in college, my classmates and I were required to complete a form called “Strong Interest Blank,” which was designed to help us choose the courses, and ultimately the major, to accomplish our vocational goals. I went in with no major or vocation in mind, but the document figured me out: I scored highest as musician-performer, musician-teacher, and social worker. After many turns and detours along the way, I ended up where that document indicated I belonged: as a singer, a teacher, and a choral conductor. After several summers as a camp counselor, and a couple of winters running a teen recreation center, I found my way to teaching public school music, and later to twenty years teaching voice and conducting choirs on the college/university level. Along the way, I spent any number of years selling my skills as a singer.

These experiences all come together in Chorale’s formation. We are an independent community of people from many backgrounds and disciplines who work together to learn good music in an intense but congenial environment. We care deeply about music of the past, and no less deeply about the composers of the present time. Composers, and their works, are our lifeline to the creative force that runs through all of us, our salvation and inspiration when the world seems overwhelmingly lonely and dark and destructive. Chorale’s singers, each in their own way, find holy release in discovering and reproducing the sounds these composers require of us, and we strive to improve our musical and vocal skills so that we can live up to their dreams and designs, which would otherwise be only dots on paper. We take seriously our obligation to engage deeply with our music, for its own sake, and to present programs which communicate our deep commitment to this art form, and which inspire and entertain our listeners.

Chorale believes that our communal efforts foster a better world, a world lifted and transformed by the greatness of which human beings are capable; a world colored by the purest expression of beauty and grace. We hope, through music, to reach deep within ourselves, and our listeners, to bypass the many distractions that litter our path, to discover the great human gift we all share. As visionary conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt wrote, “Art is not a bonus to life. It is the umbilical cord which connects us to the Divine. It guarantees our being human.”

We will present our next concerts March 23-24. Our repertoire will include Denn Er hat seinen Engeln befohlen by Felix Mendelssohn, Ich aber bin elend and Warum ist das Licht gegeben by Johannes Brahms, and Frank Martin’s Mass for Double Chorus. Fitting music to usher in the Christian Holy Week. We look forward to singing for you, both here in Hyde Park, and in Lincoln Park, on the North Side.

Wrapping up 2023 and Looking Ahead!

Chorale 2023 has drawn to a close. Our librarian, Amy Mantrone, has reshelved our Christmas music; rosters and seating charts have been revised for our next prep period, reflecting the addition of new members and the requirements of our new repertoire. The singers are taking a well-deserved break until January 3, when we reconvene.

Chorale sings a lot of newer music by living or recently deceased composers. We feel it is important that these composers be heard in conscientious, polished public performances and given the opportunity to become better known. Our recent Christmas concerts featured new, little-known music from Hungary, Iceland, England, and a composer right here in Hyde Park. Singers and listeners alike enjoyed and were enriched by music they had never before experienced.

Our Winter repertoire, in contrast, will focus on a small number of pieces by acknowledged masters: motets by Mendelssohn and Brahms and a Mass by their twentieth-century colleague Frank Martin. This Romantic music, most of it for double chorus, is difficult in predictable ways, satisfyingly rich, based on procedures and idioms with which we are all familiar. Chorale’s singers will initially be pleased to work in such familiar territory— only to discover that these composers, who wrote primarily for highly skilled instrumentalists, expect singers to be every bit as fluent musically as symphonic players. We are in for quite a ride! But buoyed up throughout by the classic, unimpeachable beauty of these works.

Our spring concerts will explore music composed in the Americas, featuring choral pieces from Cuba, Venezuela, Haiti, and First Nations Canada, as well as works from the early British settlers, the African American tradition, and established contemporary composers residing in the United States.

All of this is made possible by you, our listeners and supporters. At every step of the way, from renting rehearsal and concert venues, purchasing scores, and paying staff and licensing fees to printing posters and programs and advertising on the radio, we depend on your belief in what we do, on your generosity, and on your understanding that we are all enriched by one another. In these difficult, acrimonious times, when we live surrounded by so much strife and counterfeit emotion, music cuts through to what really matters, expresses our deepest longings, and saves us from ourselves.

Happiest of holidays to all of you, from all of us!

A Chicago Chorale Christmas

Our Chicago Chorale Christmas! concerts are almost upon us. We look forward to singing for you December 9 at St. Michael’s Catholic Church in Old Town, and December 10 at St. Thomas the Apostle Catholic Church, in Hyde Park. The notes and words are learned; our final rehearsals will be devoted to familiarizing ourselves with the venues, to pacing and continuity, to transitions. Some of our repertoire is familiar and predictable; some of it is new, with rhythmic and harmonic shifts which could catch us by surprise when we experience them in new acoustics, with new sight lines, in front of audiences. The a cappella choral art is very demanding, at times like walking on hot coals, at other times like sailing along on the most delicate of clouds. We are excited about the music we are presenting, and will do our best for you, enhancing your emotional and aesthetic experience during the coming holidays.

Repertoire is the heart and soul of Chicago Chorale’s mission. We present the best music composers have made available to us, drawn from various historical periods and national, ethnic, and religious backgrounds, with particular focus on music of the last 100 years. Chorale has no higher calling than to bring to life the creative products of these composers, to give breath and substance to their dreams and plans Part of my calling, as conductor, is to research, listen, study, make choices-- work that has fueled my blog posts over the past couple of months. The repertoire we sing defines and differentiates us. Our distinctive vocal sound and attention to aesthetic representation are byproducts of this— we strive to present what we believe the composers would want to hear from us. This makes us interesting to our supporters; it also makes it challenging and interesting to sing with us. The best conductors I have experienced and sung under have always made it very clear that we, the performers, have a holy obligation to breathe the most beautiful life we can, into the blueprints left by the composers. It is disrespectful, even blasphemous, to do less.

It was the discovery of repertoire that motivated me as a singer, pushed me to develop my voice in order to do the music, and the words, justice. Chorale exists to extend this privilege to all its members, people who love music and are willing, even compelled, to approach their music making with open ears and hearts, and willingness to do the work with commitment and discipline. We have worked hard this fall, on some beautiful music. We are eager to share the results with you.

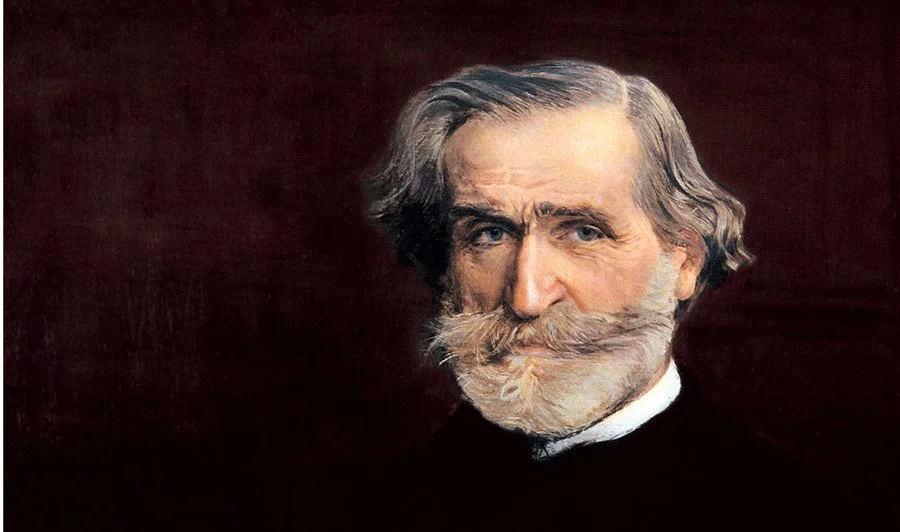

Giuseppe Verdi | Ave Maria Antiphon

The Ave Maria antiphon is recited and sung throughout the liturgical year in the Roman Catholic tradition. But it is also more specifically used during the Advent/Christmas season by Christians of all denominations, because it presents Mary’s realization that she is to become the mother of Jesus. Chicago Chorale performs at least one setting of this text every year on our Christmas concerts.

The antiphon’s text is divided into three parts. The first part consists of the Angel Gabriel’s greeting to Mary when he announces to her that she will bear a son: “And the angel came in unto her, and said, Hail, thou that art highly favored, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women” (Luke 1:28). The second part is the greeting of her cousin Elizabeth, whom she has come to visit while pregnant: “And Mary entered into the house of Zacharias, and saluted Elizabeth. And it came to pass, that, when Elizabeth heard the salutation of Mary, the babe leaped in her womb; and Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit, and cried out, saying, Blessed art thou among women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb” (Luke 1:49-42). The third part, “Holy Mary, Mother f God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death,” is not scriptural, but was added in the 15th century.

This year, Chorale is singing a setting by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), who composed it very late in his life (1889), after a career spent composing operas. It was eventually published with three other sacred choruses in Quattro pezzi sacri (Four sacred pieces), Verdi’s last major work, in 1898. Verdi did not want the Ave Maria to be performed with the other pieces, which received their premier in Paris in April 1898; but he relented later on, and the four pieces were presented as a unified work in November of that year.

Verdi was recognized in his own time, and he is in ours, as one of the most important opera composers in music history. His non-operatic compositions are few in number, and the most famous of them, his Requiem, is often referred to as an ecclesiastical opera. But his early musical training and experiences were through his parish church, where he learned to play the organ at a very young age, sang in the choir, and served as an altar boy. At the age of eight, he became the official paid organist. He turned from church music to opera in his later teens, however, and was described by his second wife as being not particularly religious.

Verdi was inspired to compose Ave Maria by the enigmatic scale C – D-flat – E – F-sharp – G-sharp – A-sharp – B – C, which Adolfo Crescentini published in Ricordi's magazine Gazetta musicale di Milano in 1889, inviting composers to harmonize it. Verdi composed a setting for four unaccompanied voices, with the bass singing the scale first, followed by alto, tenor and soprano, the three remaining voices supplying harmonic texture. Though originally intended for a quartet of soloists, the work has, from its first performance, been performed by choirs. The work’s demands are daunting: the chromatic harmonic language makes it very difficult to sing in tune, and the extreme dynamic range is difficult to navigate. I first sang it under the baton of conductor Robert Shaw, and the scores Chorale sings from contain his detailed, precise notations, designed to help the singers stay in tune.

Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming

The version of “Es its ein Ros entsprungen” (Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming) which Chicago Chorale will sing in our December concerts has a noteworthy history.

The anonymous words of this Advent hymn date back to the 14th century. They were first published in 1582 in Gebetbuchlien des Frater Conradus. The rose in the German text is a symbolic reference to the Virgin Mary. The hymn refers to the Old Testament prophecies of Isaiah, which in Christian interpretation foretell the incarnation of Christ, and to the Tree of Jesse, a traditional symbol of the lineage of Jesus. The melody, also anonymous, first appears in the Speierisches Gesangbuch in 1599. German composer Michael Praetorius (1571-1621) published his harmonization of the melody in 1609, in his sixteen-volume collection Musae Sioniae (Zion’s Music). This melody and harmonization have been the familiar, standard version of the hymn, sung through the Christian world, ever since.

Swedish composer Jan Sandström (b.1954) has taken the original , unaltered Praetorius harmonization, for mixed chorus, and composed an additional four-part “soundscape” around it which transforms the listeners’ experience. The resultant work, composed in 1990, has become one of the most performed and recorded “high-end” Advent/Christmas choral pieces of our era.

Sandström grew up in Stockholm, then studied at the School of Music in Piteå, a small city at the northern end of the Gulf of Bothnia. He later returned to Piteå in the 1980s as professor of composition. I studied at that school, myself, about thirty-five years ago, in a program called “Sommarmusik i Piteå;” Sandström was very likely teaching there at the time, though I was unaware of him. I was quite surprised to find such an institution, at what seemed like the end of the world. I don’t think the sun went below the horizon for the duration of my program, but the other participants (all of them Scandinavians) seemed nonplussed by the constant light; they were more concerned about the constant clouds of mosquitoes. I heard, and performed, a lot of wonderful music, with outstanding colleagues and in state of the art facilities. I had gone there because of an interest in Scandinavian vocal music; I returned home hooked on it.

Sandström's compositional output includes music for various ensembles: choir, opera, ballet, radio theater, and orchestra. Like most Swedes, he began his musical career as a chorister, and his work list includes a high percentage of vocal music.

Reviewer Dan Morgan commented on Sandström's setting of “Es ist ein Ros entsprungen”: "From its dark, monastic beginning rising to a radiant, multi-layered crescendo, this is the disc's crowning glory. ... It's an extraordinary fusion of old and new, a minor masterpiece that deserves the widest possible audience." Stefan Schmöe compared the "schwebende Klangflächen" (floating soundscapes) of the added second chorus to an acoustic halo. John Miller describes Sandström's addition as a "timeless, atmospheric, dream-like soundscape of poignantly dissonant polyphonic strands".

Da pacem, Domine

For the most part, I resent electronics and computers, and the fast-moving digitized life of today’s world. Turning the clocks back inspires a helpless, incoherent rage in me. I idealize a back-to -the-land existence, in which we and our community take care of our needs, grow and prepare our own food, make our own compost, develop our own culture, and make our own music. When I was in college, many of my peers shared such an ideal. Mostly, we grew out of it as we aged— but many vestiges of that dream persist in me, and lead to the interests and preoccupations that continue to matter most to me.

One huge exception to this personal Ludditism is my love of YouTube. I spend hours parked in front of my computer screen, watching and listening to musical performances which I would never see or hear otherwise. I become acquainted with individual musicians, conductors, ensembles, styles of interpretation, and repertoire I would never be aware of, without this electronic wizardry. YouTube has become my single most important resource in programming concerts and studying repertoire, especially since I stopped singing, myself. Ones personal library of recordings could never contain all that is available at the simple click of a mouse. I keep a running list of the composers, pieces, and recordings that I run across, often randomly or by accident, and make extensive use of it. I’m hooked. I find it hard to remember how I did this work without YouTube for the greater part of my career.

Among my most important YouTube finds in the past year was a recording of a new piece (2020), a setting of the Da pacem, Domine text (Grant us peace, O Lord, in our days for there is none other who will fight for us) by Hungarian composer Péter Tóth (b.1965). Sung by Cantemus vegyeskar Nyíregyháza, it was recorded in concert October 12, 2022, just one year ago. Numerous other choirs have posted recordings of the motet, all of them Hungarian. I suspect it will soon become better known, and that other postings will appear in the future.

Tóth grew up in Budapest and received his training there, at the Béla Bartók Conservatory and the Liszt Ferenc Academy. He later graduated from the Academy of Drama and Film, and has composed extensively for film and theater. His compositional style, even in this sacred a cappella setting, reflects this interest in theatrical presentation. The indicated dynamics in this piece are extreme and very expressive, and the tessitura (usual range) in the individual voice parts is quite demanding, especially of the women’s voices. His use of dramatic rhythmic ostinato in the lower voices intensifies and graphically illustrates the implied urgency and danger in the text. Effectively, he creates a dramatic scene without ever leaving the conventions of sacred a cappella music.

Tóth is currently Dean of the School of Music at the University of Szeged and is a full member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts.